March 12 2025

Ask Me by William Stafford

Some time when the river is ice ask me

mistakes I have made. Ask me whether

what I have done is my life. Others

have come in their slow way into

my thought, and some have tried to help

or to hurt: ask me what difference

their strongest love or hate has made.

I will listen to what you say.

You and I can turn and look

at the silent river and wait. We know

the current is there, hidden; and there

are comings and goings from miles away

that hold the stillness exactly before us.

What the river says, that is what I say.

March 11 2025

Assurances by William Stafford

You will never be alone, you hear so deep a sound when autumn comes. Yellow pulls across the hills and thrums, or the silence after lightening before it says its names- and then the clouds' wide-mouthed apologies. You were aimed from birth: you will never be alone. Rain will come, a gutter filled, an Amazon, long aisles- you never heard so deep a sound, moss on rock, and years. You turn your head - that's what the silence meant: you're not alone. The whole wide world pours down.

February 2 2025

When desire comes up against a wall of indifference, or gets rejected and bashed to be made small,…

stand in the want. Root in the desire.

Joshua, feel the distinction between want and need.

When I’m in need I get all eeeeeeeeee with me and please and need and “don’t you seeee meeee?” When need hits a wall then it’s a gift — a painful one, an exposure that the only actual need I have is to be shown that I am crawling instead of standing.

Desire, however, is so securely located in your being that it cannot be diminished by anyone, not even by your own self. It can be numbed (Hello I’m Joshua and I’m an alcoholic.) (Hello Joshua!), it can be ignored, but it is always there, ready and wanting to be lived.

I don’t think desire grows; I think we grow in our courage to access it, in our capacities to stand in our already desirous selves. Standing in desire changes everything, every interaction, every day. It’s a way of being, a fullness, a breathing connection to the source.

Standing in desire means that when I come up against a wall of indifference I know it has nothing to do with me. It will hurt, without a doubt, because desire and longing are inextricably bound to vulnerability. But the hurt is merely a beautiful indication that I have laid a part of me bear, making myself available to give and to receive.

To that indifference I can take my own fierce indifference, not to them as a person, but to their ambivalence.

Maintaining my desire will either transform their indifference or, if not, in this place in my life, I can take it elsewhere to where it will be met and received and enjoyed. My boys will feel it. What I make at work will be filled with it. It will radiate from me like a star gives life to a planet, affecting everything it touches.

January 25 2025

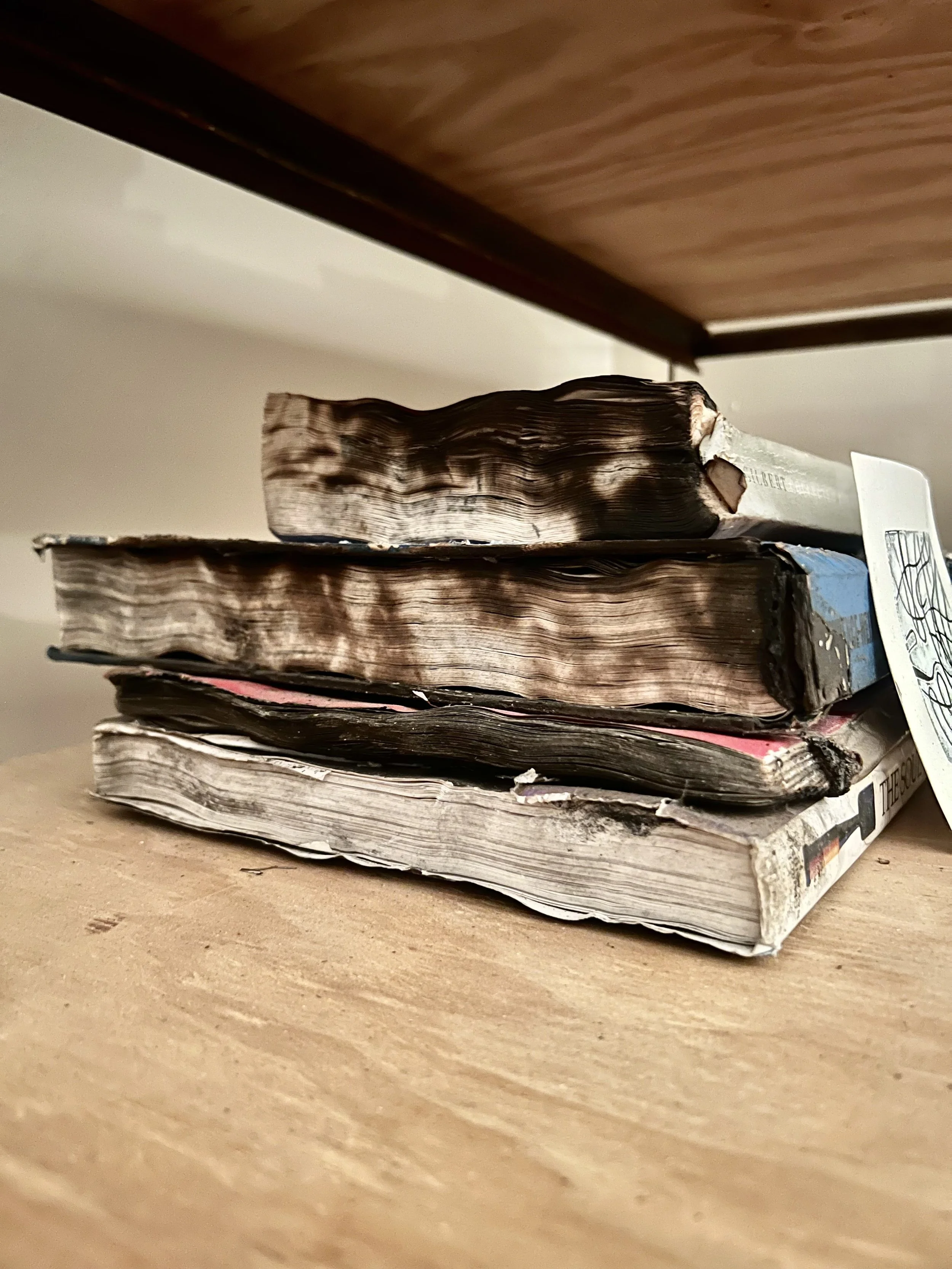

I kept the ashes from three years ago. There was a fire that burned for six months — my dog died, my woodshop burned down, my marriage ended. I was not the victim of any of it; my dog was old, my marriage’s failure was 50% on me, and my garage burning down was 100% in me. None of it was intended, but things always fall apart eventually.

I was lucky, if you can believe it. I had some good friends that counseled me to literally sit in the ashes, to let their reality pass between my fingertips and touch my tongue.

I listened, miserably, in misery. I waited. I wept and screamed and ate a lot of cookies and didn’t drink because boy did I not need to intensify the suffering. I could play that tape forward and it was not pretty.

I remember going to AA meetings during those months, and this one guy saw my grief-stricken face and asked me about it. I told him, and he smiled. I hated him so much. He said, “Oh man. You’re in it.” Then he hugged me, smiled again, and walked away.

In the ashes there are no easy answers, and anyone that gives easy answers is just asking to be punched in the throat. You’d think Captain AA Smileypants would have been the punchable one, but far from it. What else can be said except to name the fact of it all? It’s maybe the most true thing I’ve ever heard.

Now, three years later, there are still no easy answers. Answers don’t seem to be the point of anything at all. I’m no longer in the depths of it, and things have settled and are beginning to open a little. What I can tell you, miraculously, is that I now have a gratitude for the fire, and that is only possible at this point because I was willing to, and guided into, loving those ashes, loving what I could not understand, even while they were still smoldering.

•••••••••

“Like the moment you too saw, for the first time,

your own house turned to ashes.

Everything consumed so the road could open again.” (D. Whyte)

December 28 2024

Five years sober. Five years of slowly releasing the clenched fist of control, of being just slightly more conscious of when that grip tightens, then loosening each little muscle again.

Five years of listening to and telling stories in meetings of how we, together, admit we are powerless, how we are believing that a power greater than ourselves can restore us, and how we are all making daily decisions to turn our lives over to the care of God as we individually and collectively understand God.

Five years of sitting in ashes and not drinking to avoid what they have to teach. Five years of learning to celebrate myself and others without inebriating substances to intensify what already possesses more intensity than can be understood.

Five years of lying, confessing, making amends. Manipulating, confessing, making amends. Stealing, confessing, making amends. And five years of doing those things and being too stubborn or too afraid to confess and make amends.

Five years of being such a mess and being so brilliantly stunning. Of being an awful father and a phenom of a father. Of thank you, I’m sorry, I love you, forgive me. Thank you, I’m sorry, I love you, forgive me.

Five years being. That’s it. More fully, more present, more broken, more grateful, more and more my self.

Like a good friend and a good man says, “I cannot do this without you. I need all the help I can get, and you all are apart of that, so thank you. I’ll keep coming back.”

October 20 2024

I was sitting at the table with Waits after dinner. Half eaten plates of food, legos, scraps of paper, my head resting in my hands. Waits is both perceptive and nurturing. I wasn’t hiding my emotional cards, but the softness in his tone when he senses a shift tells me, a 41 year old man, that it is safe to say what I feel.

“Dad, you’ve looked sad today.”

There is a line here, a boundary, and it can be sort of nebulous, especially when emotions are steering the boat. I want to let Waits in, to let him see a vulnerable and emotional father, one who doesn’t have it all together but can still be relied upon and trusted. I don’t want him to have to take care of me. He doesn’t need to be caring for an adult man at 9 years old. So the move is how to show him where I am and not put him in a place where he has to be a caretaker, to be something he is not and should not yet be.

“Well pal, I’ve been scared. And that’s ok. Some days I’m scared and some days I’m not, and even when I’m scared I know that the three of us are in a good place,” I told him, my arms now resting on the table. He’s looking at me, taking apart legos.

“Have you cried?” he asked me. “It always helps me when I cry.”

“You know pal, I haven’t cried. I’ve wanted to cry, but the tears won’t come,” I said.

“Do you have an invisible friend?” he asked, eyebrows raised, a brightness in his face. “I talk to mine a lot and he helps me cry sometimes. Maybe you need an invisible friend!”

“Waits you’re right. I think that’s what I need.”

He grabbed some nearby paper and one of the 38 pencils that never make it back to their home.

“I know what he should look like. And I know all the things you like.”

For 10 minutes he drew, talking through all of the elements.

“His name is Cristafre.” (He said “Christopher” and spelled it the way he spelled it which is perfect.) “He wears a stocking cap and has a walking stick. This is his portal. There’s a tree because you love trees. And there’s a lamp growing out of the tree because you love to make lamps. And there is music because we are always listening to music. Everything is made out of wood. Oh and that’s a rainbow. Just because.”

• • • • • • • •

The tears still haven’t come. I don’t know why. Maybe the feeling of being scared has temporarily closed something in me. Could be a number of things. I don’t have to figure it out. What I know is that it's good for me to feel what I feel, stay present with it, not numb myself, listen to what it might have to teach, and let others in so that I don't shrink away into aloneness and the spiral of victimhood.

And here's my boy, giving me the gift of a new friend and the gift of his vulnerability of how he opens up to another.

September 20 2024

The father will be a bad father because the father has a shadow. This is unavoidable and archetypal and important. It is never an excuse for intentional bad fathering — that is cowardice.

But part of the father’s mythical place is to be a bad father. Oedipus’s father King Laius was a murderer. Abraham went to kill Issac. God betrays Jesus. This stuff is written across time.

I will be a bad father because I cannot truly see my boys. They are too similar to me and I’m unable to see myself as I am. When they anger me I am seeing myself in them, but rather than recognizing that and grieving it, instead I pout or yell or blame.

I will also be a bad father because I am scared of being a father. I am absolutely terrified and I want to leave and run away and hide. But I choose to stay, believing that I am a good father even in my bad fathering. I have to know this. I have to be reminded so that I don’t put too much pressure on myself to be something that I cannot be. That’s why I need other men around my boys who can mentor them in ways that I cannot. Mentors don’t need to worry about putting food on the table or fixing the roof, and they can see the bright goodness in my boys and can call them to more in the places I cannot.

So I lean on my brothers. I cannot do this alone. Help me live into my goodness as a father by seeing what I cannot see and saying what I cannot say. Tell me when I am showing my teeth when I should be weeping. And whisper again and again that I cannot and do not have to do it all by myself, that it’s not all on my shoulders. That’s a burden no one can bear.

September 17 2024

My boys, when wounded, need stories swimming in the currents of their bodies so that rather than becoming the wound, becoming a woe-is-me victim of the concrete world that causes their knees to bleed, instead they can reach into those river currents and pull out a story they heard at bedtime about a boy whose finger was cut and when he dipped his sore finger in a pond his finger turned to gold. Or a story about an orphan boy who was deaf and rejected by the village and then received his hearing after he took a hard fall and knocked his head against the ground.

They won’t recall these stories as they are bleeding on the sidewalk or after they are mocked on the playground by that dumb jerk kid Rusten that every parent wants to bop on the head hard enough to instill a little fear but not hard enough to involve the cops. Sorry I lost the plot here a little.

Those stories and images and ancient wisdom teach my boys what to do with the wound. If they don’t have stories then they become the wound. The wound wants to ravage them, tell them they are weak, that they have no agency. Story, however, plants the seeds of something so magical and mystical that when they are grown men they will know how to weep over and love their wounds.

That is enough to get my tired and sometimes lazy ass into their bed and tell them a tale as they drift into sleep.

May 1 2024

Yesterday after school I let the boys watch YouTube while I laid on my bed and watched YouTube. After that my oldest kid, who is 8, was all pissy and grumpy for the rest of the evening, which in turn I became pissy and grumpy at him. It’s as if I gave him a bucket of sugar and was then angry at him for being hyper.

April 24 2024

My mother died 28 years ago today. I was 12. I am 40. The song of grief never ends, but the tone most certainly shifts. Grief is dark and empty and bright and full.

The tune begins with cacophony, cymbals clashing, timpani drums, trash can lids, a baby crying, trees falling, all asynchronous and chaotic. Then silence. Total unknowing. Then it progresses into a minor key, and that could last a year or two or ten. Could be a single E minor chord or something more dissonant. There are a lot of factors and no song is the same. Maybe more silence, or maybe you can’t hear the tune for awhile, or you forget it or block it out. A tonal shift to a major key occurs after a year or two or ten, and it’s spring time, and the baby’s cry turns to laughter and then into the giggles of 6 and 8 year old boys being tickled on a bed.

The song never ends — and for me, 28 years into the music, I find myself singing, teaching my boys the tune, and dancing.

March 17 2024

I saw grief drinking a cup of sorrow and called out, “It tastes sweet, does it not?”

“You've caught me,” grief answered, “and you've ruined my business. How can I sell sorrow when you know it's a blessing?”

— Rumi, just out there in the 13th century dropping absolute bangers